Abstract

Most studies in telehealth focus on telehealth availability or use by healthcare systems or providers. Only a few behavioral studies explore determinants of individuals' continuance intention for telehealth.

This study seeks to identify factors that encourage individuals to continue the intention of using telehealth. We extended the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by examining constructs that could identify reasons individuals plan to continue using telehealth including security and privacy.

A cross-sectional survey evaluated the determinants that predicted the continuance intention of telehealth. Responses from 194 individuals were analyzed with Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling. Perceived usefulness, security, attitudes, privacy, and subjective norms were important predictors of the continuance intention of telehealth. Conversely, perceived behavioral control did not influence the continuance intention of telehealth.

The extended TPB model predicted an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth. Healthcare professionals can use these results to address individuals’ telehealth privacy and security concerns and improve their perceptions of the usefulness of telehealth. Privacy and security concerns create barriers to telehealth use that must be reduced to facilitate repeated telehealth usage in future healthcare settings.

Keywords: Telehealth; Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB); privacy; security, usefulness

Introduction

Initially, telehealth use was primarily limited to facilitating medical care in rural and underserved areas. Pre-COVID-19, telehealth use expanded with the shift to patient and quality outcomes as well as cutting costs.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth visits were often the choice for most routine physician visits. Bestsennyy, Gilbert, Harris and Rost 2 indicated that telehealth use increased from 19 percent pre-COVID-19 to 46 percent during the pandemic. Kaiser Family Foundation 3 predicts that telehealth usage in the United States (US) will continue in the post-COVID-19 era.

According to Medicaid.Gov 4 telehealth provides a low-cost, convenient alternative to face-to-face office visits. Telehealth use increases provider access, reduces travel costs and wait times, and improves continuity of care.5 Other researchers projected a potential $200 billion reduction in the cost of healthcare from the use of telehealth to manage chronic disease via remote monitoring of medical devices.6

However, many barriers to telehealth adoption exist including those related to users’ concerns about their healthcare data privacy and security,7 and the usefulness of telehealth.8 Most research studies on telehealth have concentrated on availability, telehealth use by healthcare systems, or telehealth use by healthcare providers. Few behavioral studies explore determinants of the individual’s intention to use or continuance intention of telehealth. The purpose of this study was to explore factors that can encourage individuals to use telehealth by identifying individuals’ telehealth concerns and improving their perceptions of the usefulness of telehealth.

Background

Theory of Planned Behavior

TPB is based on the social cognitive Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). Ajzen and Fishbein 9 introduced the TRA to assess what motivates an individual to behave in a certain manner based on their intention, attitudes, and subjective norms. According to TRA, an individual’s actions are influenced by their intention to act. The individual’s intentions are determined by their attitude, which is their belief that the outcome will be favorable or beneficial, and by the level of “social pressure” (subjective norm) compelling them to complete the task.

Ajzen 10 added perceived behavioral control to the TRA resulting in the TPB. The TPB has been used to explore the pathways among attitude, perceived behavior control, subjective norms, and the intention to use various healthcare systems. Bell 11 predicted the intention to use a web-based medical appointment scheduling system at a primary care medical clinic with the TPB. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Ramírez-Correa, Ramírez-Rivas, Alfaro-Pérez and Melo-Mariano 12 used the TPB to predict the intention to use telemedicine. TPB is suitable for this study because one purpose of the study is to explore the determinants of an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth. While individuals may adopt technology, their continuance intention is a better measure as it determines their decision to sustain that use of the technology rather than just using it once or only when required.13 For example, Wang, Wang, Liang, Nuo, Wen, Wei, Han and Lei 13 identified antecedents to the continuance intention of mHealth in their metanalysis/systematic review. We believe it is important to ensure that individuals are going to continue to use the tool (continuance intention) rather than a one- or two-time use as required by an event such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hypothesis Development

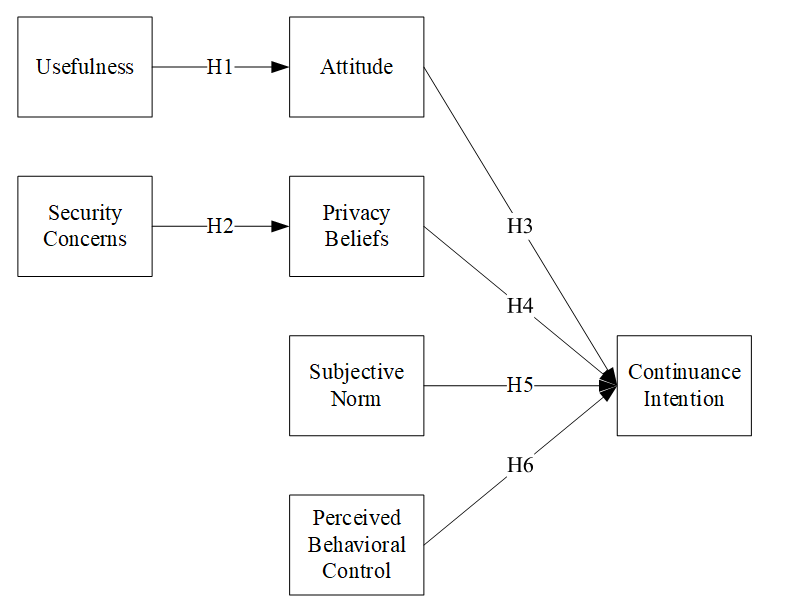

In a novel approach, we extended the TPB model by incorporating usefulness, privacy beliefs, and security concerns into the model to determine how these constructs impact the causal pathways shown in Figure 1. Few studies have included these constructs in theoretical models for the continuance intention of telehealth.

Figure 1. Model for Continuance Intention of Telehealth

Chau and Hu 8 found that usefulness positively affected attitudes when exploring the adoption of telehealth by healthcare professionals. Hsieh et. al 14 concluded that usefulness had a positive effect on attitudes toward the adoption of adoption electronic health record exchanges. Thus, we add the hypothesis:

H1: Usefulness positively influences an individual’s attitude toward using telehealth services.

Security concerns are the unease that one feels about whether their protected health information is vulnerable to risks that could disclose the information and whether protective actions are taken to guard against these threats. 15 Privacy is defined as an individual’s belief that their protected health information will only be accessed by those with a “need to know.” 16,17 Several prior researchers determined that security directly impacted an individual’s intent to adopt m-payment systems. 18 Both Kisekka et al. 19 and Moqbel, Hewitt, Nah and McLean 15 determined that security concerns negatively impacted an individual’s intention to use an e-health portal. Other researchers noted that security impacted privacy when exploring physicians’ willingness to adopt telehealth.20 For example, Elkefi and Layeb 7 investigated the benefits and challenges of telemedicine adoption for patients and caregivers after the COVID-19 pandemic and determined that security and privacy were important when studying the usability of telehealth tools. Smith, Smith, Kennett and Vinod 21 found technology barriers, including security concerns, when evaluating the telehealth use of cancer patients. Houser, Flite and Foster 22 recognized security as a challenge using telehealth. This study measured security as a risk that would be perceived as having a negative influence on an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth.15

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived security concerns negatively influence an individual’s privacy concerns about telehealth.

Attitude is present in the original TPB. Attitude refers to whether an individual feels that the outcome will favor them. Ramírez-Correa, Ramírez-Rivas, Alfaro-Pérez and Melo-Mariano 12 established that the TPB significantly predicted behavioral intention to use telehealth, with attitude having the strongest influence on behavioral intentions. Using the TPB, Kisekka, Goel and Williams 19 determined that the strongest predictor of intent to use an e-health portal was attitude. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis:

H3: Attitude positively influences an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth services.

Privacy concerns negatively impact an individual’s intention to use an e-health portal.19 Pool, Akhlaghpour, Fatehi and Gray 23 determined that elderly patients were less likely to adopt and use telehealth due to privacy concerns. Hirani, Rixon, Beynon, Cartwright, Cleanthous, Selva, Sanders and Newman 24 found that expressed privacy concerns affected whether individuals with chronic conditions used telemedicine. Zhang, Guo, Guo and Lai 25 found that privacy concerns positively impacted usefulness. While these studies explore how privacy impacts one’s use of telehealth, we believe that privacy beliefs will directly impact whether an individual will continue to use telehealth and will test the following hypothesis.

H4: Privacy beliefs positively influence an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth.

Subjective norms are the social pressures that induce individuals to take actions that meet with the approval of their peers or the approval of society. Thus, if an individual believes that society approves of their intended actions, they are more likely to perform those actions. Kisekka, Goel and Williams 19 used the TPB and determined that subjective norms strongly predicted the intention to use telehealth. Ramirez-Rivas, Alfaro-Perez, Ramirez-Correa and Mariano-Melo 26 determined that subjective norms strongly influenced the intention to use telemedicine. Thus, we add this hypothesis:

H5: Subjective norm positively influences an individual’s continuance intention of telehealth services.

Ajzen 10,Ajzen 27 suggested that perceived behavioral control impacted the intent to perform different behaviors. Self-efficacy represents “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment.” 28 Often used in the TPB, perceived behavioral control is defined as “a person’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest.” 9 Researchers have determined that self-efficacy influences perceived usefulness when examining the intention to use internet banking 30 or mobile payment systems. We posit that perceived behavior control influences perceived usefulness. 30-32 Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Perceived behavioral control positively influences an individual’s perceived usefulness of telehealth.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey study explores the factors influencing individuals' continuance intention of telehealth.

Measures

The measures for usefulness were modified from Davis 33 Privacy and security constructs were altered from studies by Dinev and Hart 34 and the remaining constructs were adapted from prior TPB studies including those by Ajzen 10

Data collection

After receiving approval from the Internal Review Board, Qualtrics Survey Service provided a panel of individuals who completed the survey utilizing our requirements. The data was collected by Qualtrics in mid-2022. Specifically, we requested survey respondents from a general population of US residents over the age of 18. We requested respondents from only one country (i.e., the US) because residents of other countries may have different perceptions of privacy. Using our specifications, Qualtrics distributed email links to a random sample of their pool who were over age 18 from the US. Qualtrics literature indicates they take steps to prevent selection bias by following up with non-responsive participants. No identifiable information was collected from the participants. The anticipated demographics were a random sample of US residents. We obtained informed consent by using a click online button within the Qualtrics survey.

Statistical Analysis

The survey construct data was analyzed using Smart PLS (Partial Least Squares) 4.0 because our predictive model was comprised of latent variables.35 Demographic data was analyzed with R statistical software version 4.1.2.36 The response rate is unknown. There were 194 valid responses from individuals over age 18 and living in the US that were analyzed. To ensure that our sample size was sufficient, we used Soper’s 37 Post-Hoc Statistical Power for Multiple Regression calculator. Soper’s 37 calculator indicated that our sample size was more than efficient based on our number of latent variables (n = 6), our R2 of .50, and our sample size of 194. See Appendix A for the survey questions.

Results

Demographics

Survey respondents included 94 females (48 percent), 99 males (51 percent), and one other (1 percent). Approximately 23.7 percent of the respondents were represented by groups ages 18-34, and the 35-50 age group accounted for 34.5 percent. The largest age group was over age 50 (41.8 percent). The largest percentage of participants held a baccalaureate degree (31.4 percent), followed by those with a high school degree (17.5 percent). The majority were employed (60.3 percent). Most had a primary care physician (95.4 percent), and 88.1 percent reported having regular doctor’s visits. Table 1 presents demographic information about respondents.

Next, study demographics are considered in comparison to the US Census 2021 data 38 and the US Census education table.39 The demographic age groups and percentages for the study respondents were 20-34 (23.7 percent) and 35-50 (34.5 percent), in comparison with the most similar Census findings the group percentages are 20-34 (20.0%) and 35-54 (25.5%). Regarding education above high school, the US Census reports high school graduates (28.3 percent), some college (17.1 percent), associate degree (9.9 percent), 4-year degree (22.2 percent), master’s degree (9.6 percent), and doctorate (1.9 percent). As expected, the current study had more respondents with associate, bachelor, master, and doctorate degrees than the US Census.

When comparing gender to the US population, Census data showed that 54.9 percent of the population are females and 45.1 percent are males. By comparison, females made up 48.5 percent of the respondents in this study, which was lower than the population, but 51 percent were males. When examining the employment rate for study respondents, 75.3 percent were employed, and 24.7 percent were unemployed. Census results for over 16 years in the civilian labor force reported lower employment (59.6 percent). There were 65.4 percent reporting annual household income less than or equal to $89,999. In similar categories, the Census found 64.2 percent reported income less than or equal to $99,999.

Table 1. Demographic Information

|

Characteristics

|

Number

|

Percentage (%)

|

|

Age, years

|

|

18-34

|

46

|

23.7

|

|

35-50

|

67

|

34.5

|

|

Over 50

|

81

|

41.8

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education (highest level)

|

|

Less than High School

|

3

|

1.6

|

|

High school graduate

|

34

|

17.5

|

|

Some college

|

22

|

11.3

|

|

2-year degree

|

29

|

15.0

|

|

4-year degree

|

61

|

31.4

|

|

Master’s degree

|

33

|

17.0

|

|

Professional Degree

|

5

|

2.6

|

|

Doctorate

|

7

|

3.6

|

|

Gender

|

|

Female

|

94

|

48.5

|

|

Male

|

99

|

51.0

|

|

Other

|

1

|

0.5

|

|

Employment Status

|

|

Full-time

|

117

|

60.3

|

|

Part-time

|

29

|

15.0

|

|

Unemployed

|

48

|

24.7

|

|

Employment Industry

|

|

Education

|

11

|

5.7

|

|

Financial Services

|

15

|

7.7

|

|

Healthcare

|

15

|

7.7

|

|

IT/Computing

|

33

|

17.0

|

|

Professional and Business Services

|

10

|

5.2

|

|

Retail

|

17

|

8.8

|

|

Other

|

93

|

47.9

|

|

Household Income

|

|

|

|

Less than $10,000

|

7

|

3.6

|

|

$10,000 - $99,999

|

22

|

11.3

|

|

$30,000 - $49,999

|

41

|

21.1

|

|

$50,000 - $69,999

|

28

|

14.4

|

|

$70,000 - $89,999

|

29

|

15.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

$90,000 - $149,999

|

44

|

22.7

|

|

More than $150,000

|

23

|

11.9

|

|

Primary Care Physician

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

185

|

95.4

|

|

No

|

9

|

4.6

|

|

Regular Doctor Visits

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

171

|

88.1

|

|

No

|

23

|

11.9

|

Measurement Model

Before analyzing the model, we assessed the constructs and survey questions for reliability and validity. To establish convergent validity, we removed items with factor loadings less than 0.70 and utilized a stepwise approach.40 A full collinearity assessment determines whether a model violates the common method bias (CMB) principles, which is variance attributed to constructs measured with the same method (e.g., the survey method). The concern is that CMB introduces false effects related only to the measurement instrument when we seek to measure the effects related to the construct being measured. Therefore, items with a variance inflation factors (VIF) value greater than 5 were removed;41 see the Factor Loadings and VIF Table located in Appendix B.

Next, we evaluated the convergent validity. Examining Table 2, we note that Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability for all items were greater than 0.70 as recommended by Nunally and Bernstein.42 These results indicate the conditions for convergent validity are met. We used two tests to confirm discriminant validity. First, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are all above 0.05.43 Discriminant validity was also confirmed using the Fornell-Locker Criterion by verifying that the square root of every AVE value for each latent construct, located on the table diagonal, was larger than the correlations with the other constructs as shown in Table 2. The results in this section offer evidence that the constructs and survey questions are reliable and valid.

Table 2. Construct reliability and validity

|

|

Cronbach's Alpha

|

rho_A

|

Composite Reliability

|

|

Average Variance Extracted (AVE)

|

VIF Squared

|

|

|

Attitude

|

Continuance Intention

|

. Usefulness

|

Perceived Behavior Control

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

Security Concerns

|

Subjective Norm

|

|

Attitude

|

0.88

|

0.90

|

0.92

|

|

0.69

|

0.83

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continuance Intention

|

0.93

|

0.93

|

0.94

|

|

0.77

|

0.61

|

0.88

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Useful

|

0.84

|

0.86

|

0.89

|

|

0.67

|

0.74

|

0.70

|

0.82

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived Behavior Control

|

0.75

|

0.78

|

0.86

|

|

0.66

|

0.60

|

0.50

|

0.54

|

0.82

|

|

|

|

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

0.86

|

0.88

|

0.90

|

|

0.70

|

0.52

|

0.57

|

0.63

|

0.48

|

0.84

|

|

|

|

Security Concerns

|

0.88

|

0.89

|

0.93

|

|

0.81

|

-0.18

|

-0.18

|

-0.22

|

-0.12

|

-0.37

|

0.90

|

|

|

Subjective Norm

|

0.74

|

0.80

|

0.85

|

|

0.67

|

0.18

|

0.26

|

0.11

|

0.16

|

0.11

|

0.15

|

0.82

|

Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 44 recommend assessing discriminant validity with the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT) as shown in Table 3. The HTMT ratio correlations are all less than 0.90, confirming discriminant validity.

Table 3. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlation

| |

Attitude

|

Continuance intention

|

Perceived Behavior Control

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

Security Concerns

|

Subjective Norm

|

Usefulness

|

|

Attitude

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continuance intention

|

0.661

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived Behavior Control

|

0.720

|

0.584

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

0.589

|

0.627

|

0.585

|

|

|

|

|

|

Security Concerns

|

0.405

|

0.426

|

0.387

|

0.658

|

|

|

|

|

Subjective Norm

|

0.232

|

0.394

|

0.379

|

0.109

|

0.569

|

|

|

|

Useful

|

0.840

|

0.782

|

0.654

|

0.726

|

0.494

|

0.202

|

|

Hypothesis Results

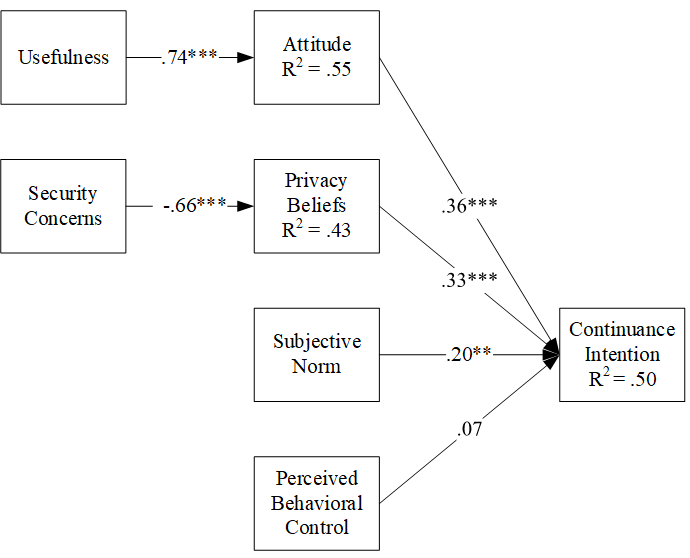

The study results demonstrated that the respondents were influenced to use telehealth by all factors in the study except perceived behavior control. Specifically, usefulness affected attitude, and security concerns influenced privacy. Attitude, privacy beliefs, and subjective norms impacted continuance intention. These results are shown in Table 4, and Figure 2.

Table 4. Hypothesis Results

| |

Original Sample (O)

|

Sample Mean (M)

|

Standard Deviation (STDEV)

|

T Statistics (|O/STDEV|)

|

P Values

|

Hypothesis

|

|

Useful à Attitude

|

0.74

|

0.75

|

0.05

|

16.48

|

0.00

|

Supported

|

|

Security Concerns à Privacy Beliefs

|

-0.66

|

-0.66

|

0.04

|

18.09

|

0.00

|

Supported

|

|

Attitude à Continuance Intention

|

0.36

|

0.36

|

0.08

|

4.55

|

0.00

|

Supported

|

|

Privacy Beliefs à Continuance Intention

|

0.33

|

0.33

|

0.07

|

4.96

|

0.00

|

Supported

|

|

Subjective Norm à Continuance Intention

|

0.20

|

0.20

|

0.07

|

2.74

|

0.01

|

Supported

|

|

Perceived Behavior Control à Continuance Intention

|

0.07

|

0.08

|

0.08

|

0.85

|

0.39

|

Not supported

|

Figure 2. Hypothesis Results

*** p < 0.001

** p <0.01

Discussion

This study is one of a small group of behavioral studies that explore determinants of individuals' continuance intention of telehealth. The results from this study can be utilized to reduce the barriers to sustained telehealth use.

Most prior studies on the adoption of telehealth did not explore security and privacy, but we felt it was important since careless security behaviors when using telehealth can cause an individual’s health information to be divulged, which invades their privacy. In this study, we found that security concerns negatively influenced an individual’s privacy beliefs.

Usefulness positively influenced attitude as previously found by Chau and Hu.8 These results are important as they indicate that individuals feel that using telehealth is beneficial. Subsequently, usefulness impacts their attitude toward the continuance intention of telehealth. According to Horn 45, a primary care physician for the Division of General Internal Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, healthcare facilities started opening their doors in June 2021. We gathered data in mid-2022. By that time, choosing to use telehealth was more of an option than a requirement. Thus, usefulness and continuance intention were measured after the height of the social distancing period for COVID-19, when individuals were returning to a less isolated existence.

Subsequently, attitude impacts an individual’s decision to continuance intention of telehealth in support of prior findings by both Chau and Hu 8 and Ramírez-Correa, Ramírez-Rivas, Alfaro-Pérez and Melo-Mariano 12 Since most individuals were attempting to social distance during COVID-19, telehealth may be seen as useful since one can visit health professionals from a safe environment.

Their privacy beliefs positively impacted whether they intended to continue to use telehealth services. A related barrier is that the patients are often responsible for acquiring the technical skills necessary for enabling and maintaining the telehealth software connection to ensure secure, private telehealth sessions. For example, in this study, over 40 percent of the respondents were over age 50, and this age group may have more difficulty managing the technical aspects of remote telehealth sessions. Thus, it is important to include privacy and security in studies on telehealth adoption.

Moqbel, Hewitt, Nah and McLean 15 found that subjective norms in the form of physicians’ and other health professionals’ encouragement impacted individuals’ decisions to use patient portals. Our results supported those prior findings. Thus, the subjective norm can be important to the adoption of systems, especially if the physician and other healthcare professionals are suggesting that patients use telehealth. We suggest that physicians continue to promote telehealth to their patients.

Surprisingly, perceived behavioral control was also not significant in our study, which contradicts the results from Chau and Hu 8 who found perceived behavior control significant but its influence was moderate. Ramírez-Correa, Ramírez-Rivas, Alfaro-Pérez and Melo-Mariano 12 also found it insignificant when exploring the adoption of telehealth in a study comparing TPB with TAM. Trafimow, Sheeran, Conner and Finlay 46 suggest that perceived behavioral control may need to be broken into two variables including perceived control and perceived difficulty. Terry and O'Leary 47 suggest that researchers should consider the differences between perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy through Ajzen 10 and Ajzen and Driver 48 propose the variables are synonymous. Thus, regardless of whether we included perceived behavior control or self-efficacy, these variables may influence the adoption and/or continuance intention of telehealth with a different group of subjects. Perhaps, COVID-19 had an impact on the individuals' perception that they did not have control over using telehealth. In many instances, physicians were requiring patients to use telehealth during this period.

Study method and design limitations are considered when interpreting any research results. Data for this study was collected with a Qualtrics Survey Service online survey instrument on a general population. Survey data is self-reported data and has an inherent bias that makes it less reliable than measured data. Specifically, respondents may underreport or overreport their reactions. They may not accurately judge the severity of the security threat or the privacy issue. Second, while efforts were made to remove those who appeared to be rushing to get through the survey, respondents may have randomly selected answers due to survey fatigue. Another limitation is that study data was only collected from an online survey.

Another limitation is the population sample size. The 194 individuals who responded to the survey were sufficient. However, larger sample sizes might have provided a better approximation of the population due to the reduction in the standard error. The respondent demographic mix must also be considered. Respondents were distributed evenly per age, employment field, and other fields as shown in Table 1.

Future research could explore other factors that might influence individuals to continue to use telehealth. One may also want to explore why perceived behavioral control was not significant. Perceived behavior control might be significant if broken into perceived difficulty or self-efficacy were used. Additionally, since fears of COVID-19 have lessened, future studies should determine individuals’ intentions to use telehealth or to continue to use telehealth, especially after this pandemic ends. Future research could include asking patients if they have any concerns about accurate diagnosis and the completeness of their physical examination when the provider uses telehealth versus in-person patient visits where the provider can conduct a hands-on examination.

Conclusion

The goal was to examine the factors that influence individuals to use telehealth. The study results indicated that privacy, security, attitude, subjective norm, and usefulness were important predictors of the continuance intention of telehealth. While perceived behavioral control was not significant in this case, the significant factors might best explain the continuance intention of telehealth.

Security initiatives for telehealth should include technology and human factors. Most telehealth visits are conducted remotely, or private information is sent through a secured format to the users over the internet using encryption or other security measures. Perhaps, healthcare organizations should educate users on security protocols when inviting individuals to telehealth sessions. The information can discuss ways to keep the session private as well as how to ensure the security of the individual’s computing device during the session.

Telehealth can provide many benefits, especially in the remote management of chronic diseases. However, privacy and security concerns of healthcare consumers create barriers to telehealth use that must be reduced to facilitate repeated telehealth usage in future healthcare settings.

Support: The study site university provided the funding for the study survey.

Acknowledgments: none

Declarations of conflict of interest: none

Appendix A

Survey Questions on Telehealth Use

|

Construct

|

Variable

|

Description

|

|

Demographics

|

Age

|

Age in years

|

|

|

EdLvl

|

Highest level of education completed

|

|

|

gender

|

Gender

|

|

|

EmpStat

|

How would you describe your employment status?

|

|

|

EmpIndustry

|

What is your occupation? - Selected Choice

|

|

|

Income

|

Household income level

|

|

|

PCP

|

Do you have a primary care physician?

|

|

|

DocReg

|

Do you regularly see a doctor?

|

|

|

CovidTelImpact

|

COVID-19 has changed how I plan to use telehealth.

|

|

|

UseTH

|

Have you used telehealth?

|

|

Attitude

|

Att1

|

My experience using telehealth to visit with my physician is positive.

|

|

|

Att2

|

Using telehealth to visit with my physician is valuable.

|

|

|

Att3

|

Using telehealth to visit with my physician allowed me to avoid getting COVID-19.

|

|

|

Att4

|

Using telehealth to visit with my physician was beneficial.

|

|

|

Att5

|

Using telehealth to visit with my physician was important.

|

|

|

Att6

|

Using telehealth to visit with my physician was satisfying.

|

|

Perceived Behavioral Control

|

PBC1

|

I have the necessary resources to use telehealth.

|

|

|

PBC2

|

I have the ability to use telehealth.

|

|

|

PBC3

|

I used telehealth because I am knowledgeable about the technology needed.

|

|

|

PBC4

|

I used telehealth because it was entirely within my control.

|

|

Subjective Norm

|

SubNorm1

|

I used telehealth because my physician suggested I use it.

|

|

|

SubNorm2

|

I used telehealth because a healthcare professional suggested I use it.

|

|

|

SubNorm3

|

I used telehealth because a friend suggested I use it.

|

|

|

SubNorm4

|

I used telehealth because a family member suggested I use it.

|

|

|

SubNorm5

|

I used telehealth because someone in my physician's office suggested I use it.

|

|

Usefulness

|

Useful1

|

I used telehealth because I could use it after business hours.

|

|

|

CUseful1

|

I used telehealth when my physician was closed due to COVID-19.

|

|

|

Useful2

|

I used telehealth even when I can’t go to the provider.

|

|

|

Cuseful2

|

I used telehealth to avoid being exposed to COVID-19.

|

|

|

CUseful3

|

COVID-19 made telehealth a useful way to see my physician.

|

|

|

Useful3

|

I used telehealth anytime I can't go to the doctor's office.

|

|

|

Useful4

|

I benefitted from using telehealth.

|

|

|

Useful5

|

The advantages of telehealth outweigh the disadvantages.

|

|

|

CUseful4

|

Telehealth was a convenient way to meet with my physician during COVID-19.

|

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

Private1

|

I believe that the information provided at a telehealth session is kept private.

|

|

|

Private2

|

When I share information during a telehealth session, it will be kept private.

|

|

|

Private3

|

When using telehealth, one is able to share information since it will be kept private.

|

|

|

Private4

|

I feel comfortable sharing information at a telehealth session because I know it is kept private.

|

|

Security Concerns

|

Secure1

|

I do not feel my health information is secure when using telehealth.

|

|

|

Secure2

|

I use telehealth because I feel that my protected health information is kept secure.

|

|

|

Secure3

|

I do not perceive that my health information is secure when using telehealth.

|

|

|

Secure4

|

I am worried that others can access my health record when using telehealth.

|

|

Continuance Intention

|

Continuance Intention 1

|

I intend to continue to use telehealth.

|

|

|

Continuance Intention 2

|

I plan to continue to use telehealth.

|

|

|

Continuance Intention 3

|

Even after COVID-19 is no longer a threat, I will continue to use telehealth.

|

|

|

Continuance Intention 4

|

I will use telehealth again.

|

|

|

Continuance Intention 5

|

Since the COVID-19 virus (coronavirus) makes it hard to see my physician, I will continue to use telehealth.

|

Appendix B

Factor Loadings and VIF

| |

Attitude

|

Continuance Intention

|

PBC

|

Privacy Beliefs

|

Security Concerns

|

Subjective Norm

|

Useful

|

VIF

|

|

Att1

|

0.74

|

0.35

|

0.32

|

0.34

|

-0.27

|

0.09

|

0.52

|

1.94

|

|

Att2

|

0.86

|

0.55

|

0.50

|

0.45

|

-0.37

|

0.17

|

0.65

|

2.71

|

|

Att4

|

0.90

|

0.60

|

0.56

|

0.55

|

-0.42

|

0.14

|

0.69

|

3.27

|

|

Att5

|

0.77

|

0.45

|

0.47

|

0.39

|

-0.35

|

0.15

|

0.58

|

1.90

|

|

Att6

|

0.86

|

0.53

|

0.59

|

0.41

|

-0.40

|

0.18

|

0.62

|

2.62

|

|

ContinuanceIntention 1

|

0.56

|

0.92

|

0.45

|

0.49

|

-0.42

|

0.28

|

0.64

|

4.55

|

|

ContinuanceIntention 2

|

0.63

|

0.93

|

0.49

|

0.56

|

-0.49

|

0.26

|

0.69

|

4.71

|

|

ContinuanceIntention3

|

0.49

|

0.86

|

0.43

|

0.44

|

-0.33

|

0.29

|

0.54

|

2.66

|

|

ContinuanceIntention 4

|

0.51

|

0.88

|

0.40

|

0.55

|

-0.52

|

0.23

|

0.62

|

2.99

|

|

ContinuanceIntention 5

|

0.47

|

0.80

|

0.40

|

0.45

|

-0.35

|

0.30

|

0.56

|

2.05

|

|

PBC1

|

0.43

|

0.31

|

0.71

|

0.35

|

-0.35

|

0.02

|

0.36

|

1.43

|

|

PBC3

|

0.47

|

0.42

|

0.88

|

0.39

|

-0.29

|

0.29

|

0.42

|

1.95

|

|

PBC4

|

0.55

|

0.47

|

0.84

|

0.43

|

-0.32

|

0.28

|

0.51

|

1.55

|

|

Private1

|

0.48

|

0.49

|

0.46

|

0.88

|

-0.61

|

0.02

|

0.58

|

2.48

|

|

Private2

|

0.43

|

0.46

|

0.39

|

0.84

|

-0.55

|

0.05

|

0.53

|

2.14

|

|

Private3

|

0.36

|

0.38

|

0.33

|

0.76

|

-0.37

|

0.08

|

0.43

|

1.74

|

|

Private4

|

0.46

|

0.55

|

0.40

|

0.87

|

-0.63

|

0.12

|

0.56

|

2.19

|

|

Sec2Rev

|

-0.56

|

-0.63

|

-0.53

|

-0.70

|

0.72

|

-0.19

|

-0.65

|

1.06

|

|

Secure1

|

-0.12

|

-0.17

|

-0.06

|

-0.30

|

0.72

|

0.33

|

-0.15

|

2.34

|

|

Secure3

|

-0.15

|

-0.14

|

-0.15

|

-0.33

|

0.76

|

0.32

|

-0.20

|

2.47

|

|

Secure4

|

-0.21

|

-0.17

|

-0.11

|

-0.36

|

0.78

|

0.42

|

-0.24

|

2.75

|

|

SubNorm2

|

0.15

|

0.23

|

0.14

|

0.08

|

0.02

|

0.57

|

0.07

|

1.03

|

|

SubNorm3

|

0.12

|

0.27

|

0.25

|

0.06

|

0.20

|

0.88

|

0.15

|

3.34

|

|

SubNorm4

|

0.14

|

0.20

|

0.22

|

0.04

|

0.20

|

0.85

|

0.14

|

3.32

|

|

Useful4

|

0.76

|

0.64

|

0.52

|

0.60

|

-0.52

|

0.16

|

0.87

|

1.99

|

|

Useful5

|

0.57

|

0.61

|

0.45

|

0.42

|

-0.34

|

0.13

|

0.81

|

1.78

|

|

CUseful3

|

0.55

|

0.50

|

0.42

|

0.54

|

-0.42

|

0.15

|

0.79

|

1.73

|

|

CUseful4

|

0.52

|

0.52

|

0.33

|

0.49

|

-0.41

|

0.05

|

0.81

|

1.92

|

References

1. Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth Benefits and Barriers. Article. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 02/01/February 2021 2021;17(2):218-221. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013

2. Bestsennyy O, Gilbert G, Harris A, Rost J. Telehealth: A quartertrillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality

3. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Coverage and Insurance. https://www.kff.org/state-category/health-coverage-uninsured/

4. Medicaid.Gov. Telemedicine. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/telemedicine/index.html

5. Majerowicz A, Tracy S. Telemedicine: Bridging Gaps in Healthcare Delivery. Journal of AHIMA. 2010;81(5):52-53,56.

6. Chacko A, Hayajneh T. Security and Privacy Issues with IoT in Healthcare. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Pervasive Health and Technology. 2018;4(14)doi:10.4108/eai.13-7-2018.155079

7. Elkefi S, Layeb S. Telemedicine’s future in the post-Covid-19 era, benefits, and challenges: a mixed-method cross-sectional study. Article. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2022:1-15. doi:10.1080/0144929x.2022.2137060

8. Chau PYK, Hu PJH. Investigating healthcare professionals' decisions to accept telemedicine technology: An empirical test of competing theories. Article. Information and Management. 2002;39(4):297-311-311. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00098-2

9. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudes and normative beliefs as factors influencing behavioral intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. January 1972 1972;21(1):1-9. US: American Psychological Association.

10. Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179.

11. Bell WF. Factors determining the behavioral intention to use a web-based appointment system: An application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB). 2022.

12. Ramírez-Correa P, Ramírez-Rivas C, Alfaro-Pérez J, Melo-Mariano A. Telemedicine Acceptance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Example of Robust Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Symmetry. 2020;12(1593):1593-1593. doi:10.3390/sym12101593

13. Wang T, Wang W, Liang J, et al. Identifying major impact factors affecting the continuance intention of mHealth: a systematic review and multi-subgroup meta-analysis. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2022;5(1):145.

14. Hsieh FY, Bloch DA, Larsen MD. A simple method of sample size calculation for linear and logistic regression. Statistics in medicine. 1998 1998;17(14):1623-1634. doi:doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1623::AID-SIM871>3.0.CO;2-S

15. Moqbel M, Hewitt B, Nah FF-H, McLean RM. Sustaining Patient Portal Continuous Use Intention and Enhancing Deep Structure Usage: Cognitive Dissonance Effects of Health Professional Encouragement and Security Concerns. Information Systems Frontiers: A Journal of Research and Innovation. 2022;24(5):1483-1496. doi:10.1007/s10796-021-10161-5

16. Myers J, Frieden TR, Bherwani KM, Henning KJ. Ethics in public health research: privacy and public health at risk: public health confidentiality in the digital age. American Journal of public health. 2008;98(5):793-801.

17. Runy L. The best line of defense: Hospitals take a proactive approach to data security threats. Hospitals and Health Networks. 2008;7(3):22-26.

18. Johnson VL, Kiser A, Washington R, Torres R. Limitations to the rapid adoption of M-payment services: Understanding the impact of privacy risk on M-Payment services. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;79:111-122. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.035

19. Kisekka V, Goel S, Williams K. Disambiguating Between Privacy and Security in the Context of Health Care: New Insights on the Determinants of Health Technologies Use. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking. 2021;24(9):617-623. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.0600

20. Luciano E, Mahmood MA, Mansouri Rad P. Telemedicine adoption issues in the United States and Brazil: Perception of healthcare professionals. Health Informatics Journal. 2020;26(4):2344-2361. doi:10.1177/1460458220902957

21. Smith SJ, Smith AB, Kennett W, Vinod SK. Exploring cancer patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ utilisation and experiences of telehealth services during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Article. Patient Education and Counseling. 10/01/October 2022 2022;105(10):3134-3142. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2022.06.001

22. Houser SH, Flite CA, Foster SL. Privacy and Security Risk Factors Related to Telehealth Services -- A Systematic Review. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2023:3-3.

23. Pool J, Akhlaghpour S, Fatehi F, Gray LC. Data privacy concerns and use of telehealth in the aged care context: An integrative review and research agenda. 2022. 2022:160. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104707

24. Hirani SP, Rixon L, Beynon M, et al. Quantifying beliefs regarding telehealth: Development of the Whole Systems Demonstrator Service User Technology Acceptability Questionnaire. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;2023(4):460–469. doi:10.1177/1357633X16649531

25. Zhang X, Guo X, Guo F, Lai K-H. Nonlinearities in personalization-privacy paradox in mHealth adoption: The mediating role of perceived usefulness and attitude. Technology & Health Care. 2014;22(4):515-529. doi:10.3233/THC-140811

26. Ramirez-Rivas C, Alfaro-Perez J, Ramirez-Correa P, Mariano-Melo A. Telemedicine Acceptance in Brazil : Explaining behavioral intention to move towards internet-based medical consultations. Conference. 2020:1-4. doi:10.23919/CISTI49556.2020.9140996

27. Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. Action control. Springer; 1985:11-39.

28. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review. 1977 1977;84(2):191-215.

29. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior : The Reasoned Action Approach. 2010;

30. Ezzi S. A theoretical Model for Internet banking: beyond perceived usefulness and ease of use. Archives of business research. 2014;2(2):31-46. doi:10.14738/abr.22.184

31. Bailey AA, Pentina I, Mishra AS, Ben Mimoun MS. Mobile payments adoption by US consumers: an extended TAM. JOURNAL. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2017;45(6):626-640. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-08-2016-0144

32. Reid M LY. Integrating Trust and Computer Self-Efficacy with TAM: An Empirical Assessment of Customers Acceptance of Banking Information Systems (BIS) in Jamaica. The Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce. 1970;13(13):1-18.

33. Davis F. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. research-article. MIS Quarterly. 09/01/ 1989;13(3):319-340. doi:10.2307/249008

34. Dinev T, Hart P. An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Information Systems Research. 2006;17(1):61-80. doi:10.1287/isre.1060.0080

35. Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker J-M. SmartPLS 4. 2022;2022(September 28, 2022)

36. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

37. Soper DS. Post-hoc Statistical Power Calculator for Multiple Regression [Software]. http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

38. Bureau UC. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates. https://data.census.gov/table?tid=ACSDP1Y2021.DP05

39. Bureau UC. Educational Attainment of the Population 18 Years and Over, by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2021. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/demo/educational-attainment/cps-detailed-tables.html

40.& Gefen D, Straub D. A Practical Guide To Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial And Annotated Example. Communications of the Association for Information systems. 2005;16(1):5. doi:https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

41.& Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing. 2019;doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

42. Nunally JC BI. Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill; 1978.

43. Fornell C, Larcker D. Structural Equation Models With Unobservable Variables And Measurement Error: Algebra And Statistics. Los Angles, CA: Sage; 1981.

44. Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd Ed.,Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.; 2022.

45. Horn DM. It’s time to go back to the doctor’s office. In person this time. The Washington Post. June 16, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/06/16/doctor-visit-physical-coronavirus-pandemic/

46. Trafimow D, Sheeran P, Conner M, Finlay KA. Evidence that perceived behavioural control is a multidimensional construct : Perceived control and perceived difficulty. British journal of social psychology. 2002;41:101-121.

47. Terry DJ, O'Leary JE. The theory of planned behaviour: The effects of perceived behavioural control and self‐efficacy. British journal of social psychology. 1995;34(2):199-220.

48. Ajzen I, Driver BL. Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leisure Sciences. 1991;13(3):185–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409109513137

Author Biographies

Diane Dolezel, PhD, MSCS, RHIA, CHDA (dd30@txstate.edu) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Health Informatics & Information Management at Texas State University, Round Rock, TX.

Barbara Hewitt, PhD (bh05@txstate.edu) is an Associate Professor and Graduate Clinical Coordinator in the Department of Health Informatics & Information Management at Texas State University, Round Rock, TX.