Abstract

Primary care physicians (PCPs) have an important role in the identification and management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). There is a paucity of research on PCPs’ practices related to the discussion of educational interventions. We conducted a retrospective chart review using Natural Language Processing to extract data on how often PCPs in an outpatient clinic: 1) discuss educational support with patients and caregivers; and 2) obtain educational records. About three-quarters of patients had at least one term related to educational support included in at least one note, but only 13 percent of patients had at least one educational record uploaded into the electronic health record (EHR). There was no association between having an educational document uploaded into the EHR and inclusion of a term related to educational support in a note. Almost half (48 percent) of these records were unclearly labeled. Further education of PCPs is warranted to increase discussions of educational support and obtaining educational records, as is collaboration with health information management professionals around labeling.

Key words: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; educational records; electronic health record; primary care pediatricians; natural language processing

Background

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is among the most highly diagnosed and treated mental health disorders in children and adolescents1. To diagnose ADHD, data from multiple sources (including educational records) are needed to demonstrate that symptoms cause functional impairment2. For youths who have ADHD, impairment in academic performance often warrants educational interventions and related instructional supports3. School supports may include environmental accommodations, modifying assignment presentation, and positive behavior support plans, to name a few4. Some youths require a greater level of support under either the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act5 or Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 19736. Primary care physicians (PCPs) are expected to be knowledgeable about these programs and services7, and have an important role in counseling caregivers of patients with ADHD on obtaining such support8.

In this study, we determined the extent to which PCPs in a single outpatient clinic bring up school supports during office visits for their patients with ADHD, and the extent to which they obtain educational records for their patients (e.g., report cards, 504 Plans, individualized education plans, etc.). We examined PCPs’ documentation within the electronic health record (EHR) to approximate their behavior in patient encounters. Previous studies have examined the EHR for PCPs’ medication prescribing practices9,10 and recommendation of behavior therapy11, additional mainstays of ADHD management. To screen PCPs’ documentation for mentions of school support, we used Natural Language Processing (NLP), which systematically breaks down text into components using algorithms, methodologies, and tools12. Previously, NLP has been used in a wide range of clinical specialties, primarily for the purposes of disease classification13.

While the aforementioned studies have involved examination of the EHR to understand PCP practices in medication and therapy recommendations for patients with ADHD, the extent to which PCPs address educational supports in patient encounters, and collect educational documentation, is unknown. Previous studies of PCPs’ practices in recommending school support have focused on different patient populations or relied on self-report of practices, for example 14,15. Given the crucial role for educational support in ADHD management, we sought to better understand PCPs’ practices in this area.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients, ages 6-18, with an ADHD diagnosis using the Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine EHR, Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI). The list of eligible patients was queried through the Virtual Data Warehouse using ICD-10 codes and SNOMED terms for ADHD. To be eligible, patients needed to attend at least two appointments for an ADHD-related or well-child office visit at a single outpatient clinic during the date range of July 1, 2018 to Dec. 31, 2019. We examined an 18-month timeframe to have the greatest opportunity of capturing multiple visits during the school year when educational documents are renewed and more easily obtained.

Patient descriptive data were extracted, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, insurance type, language preference, prescription of an ADHD-related medication, and whether they saw one of the institution’s mental/behavioral health specialists (i.e., pediatric psychology or developmental-behavioral pediatrics [DBP]) during the study period. We also determined whether patients had neurodevelopmental disorders with high rates of comorbidity to ADHD, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), specific learning disorder (SLD), and intellectual disability (ID). These were queried using the relevant ICD-10 codes.

To review provider notes for documentation of ADHD-specific educational support terms, encounter notes were electronically extracted from the EHR for analysis using Canary Natural Language Processing (NLP) Software. Canary was selected due to its performance compared to other software and NLP models16. Testing of the NLP algorithm was completed using a test sample of 50 notes (outside the timeframe of the study) known to include at least one of the search terms. The analysis was run iteratively until all instances of the chosen study terms were identified. For the full study data set, we reviewed appointment documentation for 25 percent of the subjects (15 percent of total notes) for accuracy of the NLP algorithm.

From these data, we determined the frequency with which educational support terms were documented in providers’ notes. Dependent on sample size, the following categorical variables were analyzed using Chi square or Fisher’s tests: gender, race, ethnicity, ADHD medication prescription, specialist involvement, comorbid diagnoses, insurance category, and presence of uploaded educational support documents. Age was the only continuous variable. It was not normally distributed; therefore, a Wilcoxon Rank Sum analysis was performed. All NLP-related analyses were performed using SAS v 9.4.

In addition, we manually screened all uploaded documents in patients’ EHRs within the study period for educational documents, including those related to special education. We then determined whether the pertinent documents had been assigned clear titles in the EHR for ease of identification by clinicians. Clearly labeled documents were defined as those that had a match between the title on the originating document and the file upload title. To ensure data validity, a senior author cross-checked 10 percent of the data set. A concordance rate of 77.42 percent was achieved and the discrepancies were reconciled through consensus.

We used multivariable logistic regression models to determine patient factors associated with having at least one educational record uploaded into the EHR. The logistic regression model was fit with seven patient factors including sex, age, ADHD medication prescription, specialist involvement, and comorbid diagnoses (ASD, SLD or ID). Insurance, race, and ethnicity were not included in the model due to the small sample size in certain categories. We also calculated the odds ratios (OR) for interpretation of the results. Logistic regression analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.0.0).

The Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study and informed consent was waived as the study involved no more than minimal risk to the subjects and appropriate steps were taken to ensure confidentiality.

Results

During the 18-month timeframe, 314 unique patients were identified with a total of 1,459 ADHD-related visits. On average, each patient had 4.6 visits (SD=2.4). The mean age was 11.2 years (SD=3.39 years), 69.7 percent were male, 99.4 percent indicated their preferred language was English, and 76.4 percent had public insurance. Approximately 90 percent of the patients were prescribed an ADHD medication, 64.3 percent had seen a behavioral health specialist at our institution, and 13.4 percent had a comorbid neurodevelopmental diagnosis. See Table 1 for details of the patient sample.

Overall, 231 (73.57 percent) patients had at least one mention of educational support in a clinical note during the study timeframe. The most frequently used educational terms for each patient are listed in Table 2.

Engagement with a behavioral health specialist increased the odds that a patient had at least one educational term included in at least one note (p<0.01). Race was significant with more White patients than Black patients having a mention of educational support in their notes (p<0.05) (Table 3). There was also a significant difference in age, with younger children more likely to have educational terms documented (M=10.94 years, SD=3.31 years for those with documentation compared to M=11.98 years, SD=3.53 years for those without; p<0.05). There was no association between inclusion of an educational support term in the encounter note and having an educational record uploaded into the EHR (p=0.4852).

A total of 64 uploaded educational records were identified in the EHR (see Table 4). Forty-one patients (13 percent) had at least one type of educational record uploaded into the EHR. Engagement with a behavioral health specialist increased the odds that a patient had at least one educational record uploaded to the EHR by 2.7667 times (p<0.05). One-unit increase in age decreased the odds that a patient had at least one educational record uploaded into the EHR by 0.9844 times (p<0.05).

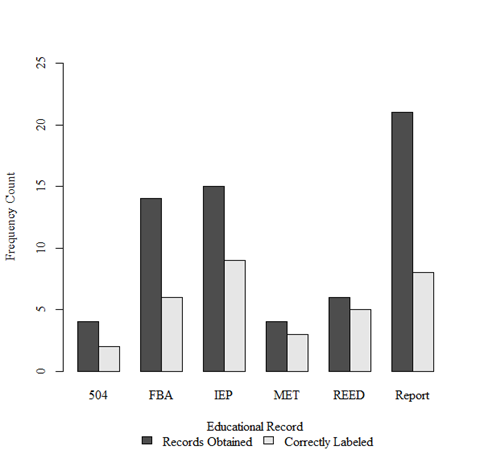

Fifty-two percent of educational records were clearly titled within the EHR. See the Figure for details on the number of records obtained and labeling for each type of document. Unclear or incorrect titles were most often “outside correspondence” or an arbitrary document identification number. Some were also incorrectly labeled as a different type of educational document.

Figure: Educational Records Correctly Labeled in Electronic Health Record

Legend:

504=504 Plan

FBA=Functional behavioral assessment or behavior plan

IEP=Individualized education program

MET=Multidisciplinary evaluation team report

REED=Review of existing evaluation data

Report=Report card or progress report

Discussion

We examined PCPs’ notes for pediatric patients with ADHD at an outpatient clinic to determine the extent to which they addressed educational support and obtained educational records during patient encounters. Overall, one-quarter of patients did not have any terms related to educational support in any of their notes, suggesting their PCP did not discuss this in either initial or ongoing treatment planning. This is concerning as educational interventions are recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) as part of the treatment of ADHD. Furthermore, only a minority of patients had any educational records uploaded to their EHR. There was no association between the presence of an educational document in a patient’s chart and the inclusion of an educational support term in at least one note.

White patients and younger patients were more likely to have at least one educational support term included in a note, suggesting PCPs in our clinic addressed supports more with these populations. Younger patient age and involvement of a mental/behavioral health specialist increased the odds that educational records were uploaded. This may reflect PCPs’ assumptions that older patients already have established educational supports so therefore do not discuss supports or solicit updated educational records. Studies on race and disproportionality in special education have yielded inconclusive results17, but our small study would suggest that PCPs are less likely to counsel caregivers of Black youths on obtaining educational support, thus resulting in an incomplete discussion of ADHD treatment components. Future research could investigate the relationship of patient race, age, and PCPs’ practices in recommending educational supports.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the presence of educational records in the EHR. This involved manual screening of each document uploaded during the study timeframe. This reflects the burden on investigators as well as clinicians; the EHR can contain many records, which may be either unclearly labeled or comprise hundreds of pages without clear document boundaries, making it hard to find specific records18,19. Another limiting factor of conducting research on uploaded documents in the EHR is that such documents are often viewable only in a specific institution’s context, and not to researchers in other institutions who may share an EHR20. Often, the documentation is stored as a PDF or another image format, which does not export easily for database inclusion/analysis21.

Our study also revealed the challenges of identifying records due to inconsistent health information management (HIM) standard labeling practices when adding documents into the EHR, necessitating manual search through numerous uploaded documents. In our study, only about half of the relevant documents had upload titles congruent with the originating document. In the future, appropriate training of HIM staff on the labeling of received educational records will allow more efficient access for clinicians (and researchers). Another approach would be using NLP approaches to reduce the burden of having to manually name and add individual educational records, though it is easier to conduct NLP with text than uploaded documents as the latter may require both NLP and optical character recognition with machine learning22. It may also help to provide a separate “tab” for educational information, like that which exists for laboratory and radiologic information.

Some limitations to our study include the fact that data were only from a single, small institution in the Midwest, and therefore reflected local practices that may not be generalizable to other locations or organizations. Also, given the retrospective chart review design, we assumed PCP behavior by their EHR documentation where inclusion of terms was used as a proxy for discussion of such topics during the actual encounter, which may not have reflected all actions or discussions that occurred during the encounter. There may be some instances when a PCP did obtain educational records and review them, but they were not saved to the EHR due to the PCP returning them to the family without obtaining a copy, or due to an uploading error.

Future studies should evaluate methods of care coordination that may enhance the number of records obtained. Often the burden of coordinating care falls to the caregiver, which is challenging to navigate for those unfamiliar with such processes or coping with multiple stressors and limited resources23. Teachers and caregivers both express an interest in sharing educational documentation with PCPs, and there have been some efforts to integrate medical and educational records24. However, school districts’ electronic management systems for educational documentation are not always interoperable with medical EHRs. There is also the issue of the two privacy laws, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)25 for medical settings, and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)26 for school settings, which may be perceived as a barrier to sharing information. We suggest that while PCPs have tools available for ongoing treatment monitoring (e.g., follow-up rating assessments for parent and teacher), collection of educational information should be considered another “vital sign” of treatment as it provides valuable information about child academic and behavioral functioning. Pending any efforts for interoperability between school electronic systems and EHRs, this will require care coordination and system-level efforts as current ADHD portals also are unable to import educational data other than teacher rating scales (e.g., mehealth for ADHD tool)27.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that PCPs do not appear to consistently address educational supports during visits with patients with ADHD based on NLP analysis. Furthermore, PCPs do not obtain educational records for most patients with ADHD, though involvement of specialists did increase the likelihood the records were obtained. There are currently several barriers to obtaining and locating educational records in the EHR, which need to be addressed for PCPs to advocate for families and optimize the care of pediatric patients with ADHD. Additionally, while NLP improves the efficiency of EHR analysis, caution should be exercised when interpreting results of these analyses as documentation may not be a true reflection of topics discussed at the visit.

Disclosures: None of the authors have any potential financial conflicts of interest related to the content of this manuscript. No funding was received for this work.

References

- Costello EJ, He JP, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatr Serv. 2014; 65(3):359-366.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

- Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019; 144(4).

- Pfiffner L, DuPaul G. Treatment of ADHD in School Settings. In: RA Barkley, ed. . 4th ed. New York: The Guildford Press; 2015: . In: Barkley R, ed. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. Guilford; 2015:596-629.

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 20USC X1400.; 2004.

- United States Office for Civil Rights. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.; 1973.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Children With Disabilities. The Pediatrician’s Role in Development and Implementation of an Individual Education Plan (IEP) and/or an Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP). Pediatrics. 1999; 104(1):124-127.

- Lipkin PH, Okamoto J, Norwood KW, et al. The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) for Children With Special Educational Needs. Pediatrics. 2015; 136(6):e1650-e1662.

- Kazda L, Bell K, Thomas R, McGeechan K, Sims R, Barratt A. Overdiagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Scoping Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(4):e215335-e215335.

- Morkem R, Patten S, Queenan J, Barber D. Recent Trends in the Prescribing of ADHD Medications in Canadian Primary Care. J Atten Disord. 2017; 24(2):301-308.

- Bannett Y, Gardner RM, Posada J, Huffman LC, Feldman HM. Rate of Pediatrician Recommendations for Behavioral Treatment for Preschoolers with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Diagnosis or Related Symptoms. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 176(1):92-94.

- Joseph S, Hlomani H, Letsholo K, Kaniwa F, Sedimo. K. Natural language processing: A review. Int J Res Eng Appl Sci. 2016; 6(3):207-210.

- Koleck TA, Dreisbach C, Bourne PE, Bakken S. Natural language processing of symptoms documented in free-text narratives of electronic health records: a systematic review. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2019; 26(4):364-379.

- Masterton JM, Savage TA, Walsh SM, Guzman AB, Shah R. Improving Referrals to Preschool Special Education in Pediatric Primary Care. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2021; 35(5):461-470.

- Sheppard ME, Vitalone-Raccaro N. How physicians support children with disabilities and their families: Roles, responsibilities and collaborative partnerships. Disabil Health J. 2016; 9(4):692-704.

- Malmasi S, Ge W, Hosomura N, Turchin A. Comparing information extraction techniques for low-prevalence concepts: The case of insulin rejection by patients. J Biomed Inform. 2019; 99:103306.

- Cruz RA, Rodl JE. An Integrative Synthesis of Literature on Disproportionality in Special Education. J Spec Educ. 2018; 52(1):50-63.

- Kostrinsky-Thomas AL, Hisama FM, Payne TH. Searching the PDF Haystack: Automated Knowledge Discovery in Scanned EHR Documents. Appl Clin Inform. 2021; 12(02):245-250.

- Goodrum H, Roberts K, Bernstam E V. Automatic classification of scanned electronic health record documents. Int J Med Inform. 2020; 144:104302.

- Payne TH, Lovis C, Gutteridge C, et al. Status of health information exchange: a comparison of six countries. J Glob Health. 2019; 9(2).

- Hsu E, Malagaris I, Kuo Y-F, Sultana R, Roberts K. Deep learning-based NLP data pipeline for EHR-scanned document information extraction. JAMIA Open. 2022; 5(2).

- Hom J, Nikowitz J, Ottesen R, Niland JC. Facilitating clinical research through automation: Combining optical character recognition with natural language processing. Clin Trials. 2022; 19(5):504-511.

- Power TJ, Michel J, Mayne S, et al. Coordinating systems of care using health information technology: development of the ADHD Care Assistant. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2016; 9(3-4):201-218.

- Michel JJ, Mayne S, Grundmeier RW, et al. Sharing of ADHD Information between Parents and Teachers Using an EHR-Linked Application. Appl Clin Inform. 2018; 9(4):892-904.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

- Epstein JN, Langberg JM, Lichtenstein PK, Kolb RC, Simon JO. The myADHDportal.Com Improvement Program: An innovative quality improvement intervention for improving the quality of ADHD care among community-based pediatricians. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2013; 1(1):55-67.

Tables & Figures

Table 1: Patient Characteristics (N = 314)

|

Characteristic

|

Variable

|

n (%)

|

|

Sex

|

Male

|

219 (69.7)

|

|

Female

|

95 (30.3)

|

|

Race

|

White or Caucasian

|

186 (59.2)

|

|

Black or African American

|

99 (31.5)

|

|

Multiracial

|

16 (5.1)

|

|

Unknown

|

5 (1.6)

|

|

Other

|

8 (2.5)

|

|

Ethnicity

|

Hispanic/Latinx

|

21 (6.7)

|

|

Not Hispanic/Latinx

|

285 (90.8)

|

|

Unknown

|

8 (2.5)

|

|

Preferred Language

|

English

|

312 (99.4)

|

|

Sign language

|

1 (0.3)

|

|

Unknown

|

1 (0.3)

|

|

On ADHD Medication

|

Yes

|

283 (90.1)

|

|

No

|

31 (9.9)

|

|

Insurance

|

Commercial

|

70 (22.3)

|

|

Public

|

240 (76.4)

|

|

Self-Pay

|

4 (1.3)

|

|

Seen By Specialist

|

Yes

|

202 (64.3)

|

|

No

|

112 (35.7)

|

|

Has an Additional Diagnosis

|

Autism Spectrum Disorder

|

20 (6.4)

|

|

Specific Learning Disorder

|

16 (5.1)

|

|

Intellectual Disability

|

6 (1.9)

|

Note: “Specialist” refers to developmental behavioral pediatrics or pediatric psychology

Table 2. Frequency of educational terms in notes by patient.

|

Term

|

Patients with mention in note, N (# patients)

|

Percent of patients with mention in note, % (N/231)

|

|

1:1 Aide/One-to-One Aid/Aide

|

13

|

5.63%

|

|

Accommodations

|

5

|

2.16%

|

|

Paraprofessional/Parapro

|

4

|

1.73%

|

|

Academic Intervention Service/AIS

|

1

|

0.43%

|

|

Academic Learning Plan/ALP

|

2

|

0.87%

|

|

504 Plan/504

|

99

|

42.86%

|

|

Individualized Education Plan/IEP

|

179

|

77.49%

|

|

School Assessment

|

1

|

0.43%

|

|

School Testing

|

1

|

0.43%

|

|

School Evaluation

|

5

|

2.16%

|

|

School Support

|

0

|

0.00%

|

|

School Programming

|

26

|

11.26%

|

|

Special Education

|

32

|

13.85%

|

|

Resource Room

|

3

|

1.30%

|

|

Behavioral Intervention Plan

|

12

|

5.19%

|

|

Functional Behavioral Analysis

|

0

|

0.00%

|

|

Psychoeducational

|

1

|

0.43%

|

Table 3. Frequency of educational support note documentation by characteristic.

|

Characteristic

|

Variable

|

Educational support term included in note

n (%)

|

Educational support term not included in note

n (%)

|

p-value

|

|

Sex

|

Male

|

165 (75.3)

|

54 (24.7)

|

0.2787

|

|

Female

|

66 (69.5)

|

29 (30.5)

|

|

Race

|

Multiracial

|

9 (56.3)

|

7(43.8)

|

0.0198*

|

|

Black

|

73(73.7)

|

26 (26.3)

|

|

White

|

140 (75.3)

|

26 (14.0)

|

|

Other

|

6 (75.0)

|

2 (25.0)

|

|

Unknown

|

3 (60.0)

|

2 (40)

|

|

Ethnicity

|

Hispanic

|

19 (90.5)

|

2 (9.5)

|

0.1688

|

|

Not Hispanic

|

206 (72.3)

|

79 (27.7)

|

|

Unknown

|

6 (75.0)

|

2 (25.0)

|

|

Prescribed ADHD Medication

|

Yes

|

211 (74.6)

|

72 (25.4)

|

0.2823

|

|

No

|

20 (64.5)

|

11 (35.5)

|

|

Seen By Specialist

|

Yes

|

163 (80.7)

|

39 (19.3)

|

0.0001*

|

|

No

|

68 (60.7)

|

44 (39.3)

|

|

Comorbid Diagnosis

|

Yes

|

33 (84.6)

|

6 (15.4)

|

0.0945

|

|

No

|

198 (72.0)

|

77 (28.0)

|

|

Insurance

|

Public or Self-pay

|

185 (75.8)

|

59 (24.2)

|

0.0910

|

|

Commercial

|

46 (65.7)

|

24 (34.3)

|

|

Uploaded Educational Record

|

Present

|

32 (78.0)

|

9 (22.0)

|

0.4852

|

|

Not present

|

199 (72.9)

|

74 (27.1)

|

Note: *Significance at p<0.05

Table 4. Educational records upload frequency.

|

Document Type

|

N

|

|

Review of Existing Evaluation Data

|

6

|

|

Eligibility Recommendation

|

0

|

|

Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team Report

|

4

|

|

Individualized Education Program Report

|

15

|

|

IEP Progress Report OR Report Card

|

21

|

|

504 Plan

|

4

|

|

Functional Behavioral Assessment

|

14

|

|

Behavior Support Plan

|

0

|

Author Biographies

Katherine Tennant Beenen, PhD (Corresponding Author)

Division of Pediatric Psychology, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

katherine.beenen@wmed.edu

Nicole Garton, MD

Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Resident Physician

nicole.garton@wmed.edu

Emily Carroll, BA

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Medical Student

emily.carroll@wmed.edu

Ashley Tang, BS

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Medical Student

ashley.tang@wmed.edu

Shamsi Berry, PhD

Department of Biomedical Informatics

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Associate Professor

shamsi.berry@wmed.edu

Kevin H. Lee, PhD

Department of Statistics

Western Michigan University

Assistant Professor

k.lee@wmich.edu

Theresa McGoff, MBA, RN

Department of Biomedical Informatics

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Data Manager

theresa.mcgoff@wmed.edu

Neelkamal Soares, MD

Division of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine

Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

Division Chief and Professor

neelkamal.soares@wmed.edu