Abstract

Purpose: The study purpose was to describe the availability of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation (SOGI) data in a large, Catholic health system.

Methods: A retrospective chart review on the Sisters of St. Mary (SSM) Health database was conducted from January 1, 2012, to March 27, 2024. The availability of SOGI data and number of sexual and gender minority patients was reported.

Results: Among the 5,759,869 records, data on sex was available for the majority of the population (99.9 percent); data on gender identity and sexual orientation were reported for smaller proportions (7.4 percent and 4.5 percent, respectively). Sex and gender were reported among 7.4 percent of the population. A total of 4,567 gender minority and 14,644 sexual minority patients were seen.

Conclusion: Though SOGI data were largely unavailable in the SSM Health database, the system has the capacity to separately record sex, gender, and sexual orientation, with a range of response options to capture gender and sexual orientation diversity.

Keywords: sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, demographic data

Introduction

Sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity (SOGI) are essential, demographic patient data.1 The American Medical Association (AMA) defines sex or sex assigned at birth based on a subjective evaluation of external anatomic structure(s) and its comparison to various sex categories, whereas gender identity describes how people conceptualize themselves as gendered beings, including one’s innate and personal experience of gender. Sexual orientation describes an inherent or immutable enduring emotional, romantic or sexual attraction to others.2 Definitions of these key terms may vary among countries, cultures, and time periods.3

Recommendations for SOGI Data Collection

SOGI data are often conflated or omitted in clinical, research, and administrative settings. This practice undermines the accuracy and validity of patient data and resulting datasets for research purposes.2 Accurate data collection is essential for all patients, but especially sexual and gender minority patients (SGM) who may otherwise be excluded. Sexual minority patients are those who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or pansexual or who are attracted to or have sexual contact with people of the same gender; gender minority patients are those whose gender identity (man, woman, other) or expression (masculine, feminine, other) differs from their sex assigned at birth (male, female).4 They may identify as transgender, gender queer, non-binary, or something other than their sex assigned a birth.

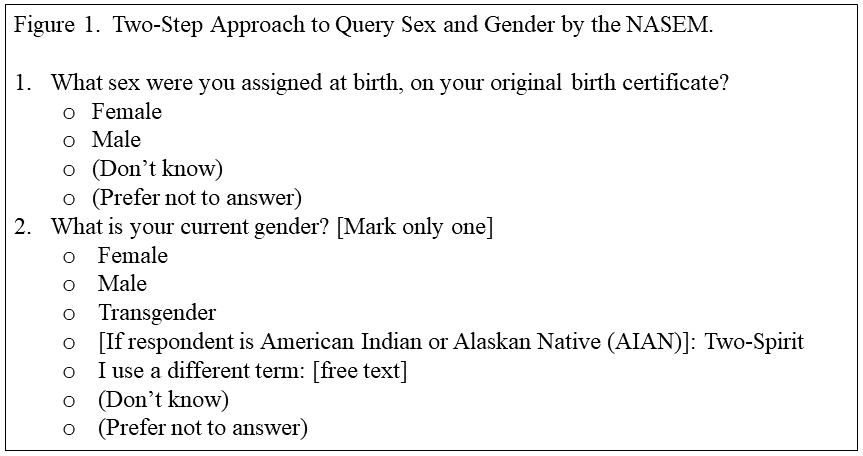

Leading organizations such as the AMA, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), and the Biden-Harris Administration have underpinned the importance of accurately distinguishing between these terms to ensure precision in data collection and reporting.1,2,5 National and international surveys have utilized a two-step approach to separate query sex and gender, such as the censuses in Canada, England and Wales, New Zealand, and Scotland, among others.1 In the United States, the NASEM published recommended language for the two-step approach with a separate question to query intersex status (Figure 1). A breadth of gender identity response options were recommended to capture gender diversity (i.e. transgender, two-spirit), as well as options to enter free text, “don’t know,” or “prefer not to answer.”1

Religiously Affiliated Institutions

These recommendations present a unique question for religiously affiliated institutions where entities have asserted conflicting comments surrounding the healthcare of SGM patients. For example, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a mandate against gender-affirming medical interventions for gender minority patients at Catholic hospitals, which contradicts standards of care from international and national health organizations.3,6,7

Regardless of whether gender-affirming medicine occurs in Catholic healthcare settings, whether these institutions are collecting and reporting SOGI data on their patient population has yet to be explored. SGM patients may still utilize religiously affiliated medical care facilities for routine, urgent, and emergent needs, like any other patient, though perhaps with greater frequency given known health disparities in cancer, chronic illnesses, infectious disease and mental health.8

Study Purpose and Aims

The purpose of this study was to describe the reporting of SOGI patient data in a large, Catholic health system. The objectives were to: describe availability of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation data; and report the number of SGM patients captured in the health system.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective chart review of the Sisters of St. Mary (SSM) Health System patient population. This method was selected for its appropriateness of fit with the study purpose and aims focused on data availability.9 The checklist by the Professional Society for Health Outcomes and Research (ISPOR) Task Force on Retrospective Databases was used to ensure methodological quality.10

SSM Health Database

SSM Health is a Catholic, non-profit integrated care network operating in Missouri, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin in the United States. The network includes 12,800 providers, 23 hospitals, 300 physician offices, outpatients, and virtual are services, and 13 post-accurate facilities.11 The SSM Health electronic health record (EHR) database, EPIC Clarity, is a subset of the SSM Health patient data that is available for research purposes and stored in Microsoft SQL.12 The database contains records on over 11 million patients.

The database was queried for sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation data among all patients ages 12 or older during years January 1, 2012, to March 27, 2024. Age 12 was selected as a cut-off as it is often used as a research standard for adolescence and often coincides with puberty13 and gender identity development.14 Records were included if the patient had at least one encounter in the system within the study period. Patients were excluded if they did not have an encounter during the study period or if they were younger than 12 years old at the time of the pull.

Sex was reported as female, male, other, unknown, or null. Gender identity was reported as female, male, transgender female, transgender male, gender nonconforming, genderqueer, other, choose not to disclose, or null. Sexual orientation was reported as straight, gay, lesbian, lesbian or gay, bisexual, multiple listed, don’t know, something else, choose not to disclose, or null. Null indicated the data was unavailable, or not reported in the system.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. A very low prevalence was reported as <1.0.

Results

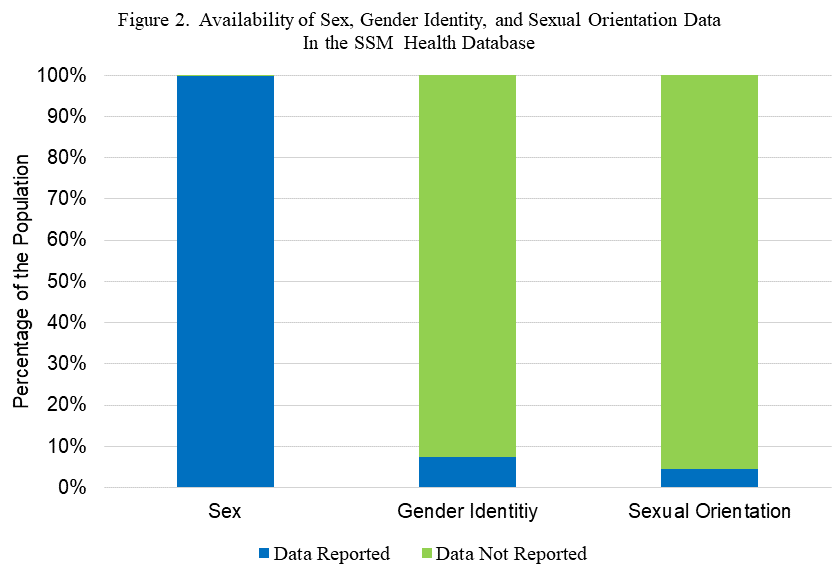

A total of 5,759,869 records were included in the analysis; 5,165,056 records were excluded due to lack of encounters in the system during the study period. Figure 2 depicts the availability of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation data. Data on sex was available in the majority of the population (99.9 percent), while data on gender identity was available for a small proportion (7.4 percent). Both sex and gender data were reported among 7.4 percent of the population. Data on sexual orientation was reported in a smaller proportion of the population (4.5 percent).

The sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation of the population is depicted in Table 1. Regarding sex, patients were mostly female (53.7 percent) or male (46.2 percent), with small proportions of patient data that was reported as unknown, “other,” or unavailable (<1.0 percent). Although gender identity data was unavailable for most patients (92.6 percent), a total of 4,567 patients, or 0.08 percent of the population identified as a gender minority (transgender female or transgender male, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, or “other.”) Regarding sexual orientation, although data was unavailable for most patients (95.4 percent), a total of 14,644 patients, or 0.25 percent of the population identified as a sexual minority (gay, lesbian, bisexual, or “something else.”)

Discussion

Gender identity and sexual orientation data were largely unavailable from the SSM Health database. This reflects larger trends in national surveys where SOGI data are largely omitted, or where sex and gender are conflated and limited to a male-female binary.1,5,15 Promisingly, the database includes the fields of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation, with a range of response options to capture gender and sexual orientation diversity. This suggests that the gap in data availability is occurring at the provider level where SOGI data is not routinely collected, rather than the database level that limits its availability. Provider education or recommendations from the network may improve demographic data collection practices. Future studies may track the frequency of SOGI data collection over time, the impact of provider education and network recommendations on data collection practices, the accuracy of SOGI data collection and reporting, and the number of sexual and gender minority patients cared for by SSM Health.

SSM Health cared for over 14,000 sexual minority patients and over 4,000 gender minority patients from January 1, 2012, to March 27, 2024, though these estimates are likely low. It is also probable that SOGI data were not collected in certain patient encounters where the data seemed irrelevant to the nature of care provided. For example, data on sexual orientation may not have been collected in an emergency room encounter for a fractured bone. The NASEM recommends collecting only necessary data to meet a defined purpose. Thus, a proportion of unavailable data may have reflected its lack of relevance to the encounter.

Routine SOGI data collection in Catholic healthcare settings will ensure that, at minimum, SGM patients are accurately counted. Administrators of Catholic health institutions must consider how they will adhere to standards of care for their SGM patients, while also responding to conflicting guidance from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

Strengths of this study were the large study population across multiple states and the long observation period. One limitation was the potential discrepancy between clinical intake procedures, which likely vary by site and provider, and how data is reported in the SSM Health database; for example, providers may be routinely collecting SOGI data, but the language of the questions may differ from that of the database. A final limitation was the generalizability of the study findings to the Midwestern United States or similar health networks with a Catholic affiliation. Future research may explore the SOGI data collection practices in other regions of the United States and at institutions with various religious affiliations.

Lastly, future research is needed to explore how data collection and reporting practices respond to the government’s charge to improve SOGI data in the United States.6 Given that approaches may vary by agency, studies can report the data collection and reporting practices adopted.

Conclusion

Though SOGI data were largely unavailable in the SSM Health database, the system has the capacity to separately enter sex, gender, and sexual orientation, with a range of response options to capture gender and sexual orientation diversity. Provider education and recommendations from the network are needed to ensure SOGI data are treated as routine, essential demographic data.

Authors’ Contributions: Chrusciel facilitated the data pull and synthesis. Linsenmeyer drafted a first draft of the article. All authors reviewed the article, provided comments, and agreed on the final draft.

Acknowledgements: This work is supported by work from the Saint Louis University School of Medicine and resources from the Advanced HEAlth Data (AHEAD) Research Institute. Irene Ryan of the AHEAD Institute completed the data pull and synthesis.

Statement on Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Measuring sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. National Academies Press, Washington, DC (2022).

2. American Medical Association. Advancing health equity: A guide to language, narrative and concepts. Published 2021. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/ama-aamc-equity-guide.pdf

3. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int J Transgend Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259.

4. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Adolescent and School health. Health considerations for LGBTQ youth: Terminology. Reviewed December 23, 2022. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/terminology/sexual-and-gender-identity-terms.htm

5. National Science and Technology Council, Subcommittee on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Variations in Sex Characteristics (SOGI) Data, Subcommittee on Equitable Data. Federal Evidence Agenda on LGBTQI+ Equity. Washington, DC (2023).

6. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Committee on Doctrine. Doctrinal note on the moral limits to technological manipulation of the human body. Published March 20, 2023. Accessed July 18, 2023. https://www.usccb.org/resources/Doctrinal%20Note%202023-03-20.pdf

7. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Feb 1;103(2):699] [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jul 1;103(7):2758-2759]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

8. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health. Reviewed November 3, 2022. Accessed July 20, 2023.

9. Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:12.

10. SSM Health. Our heritage of healing. Publication date unknown. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ssmhealth.com/resources/about/mission-vision-values/our-heritage

11. Motheral B, Brooks J, Clark MA, et al. A checklist for retrospective database studies--report of the ISPOR Task Force on Retrospective Databases. Value Health. 2003;6(2):90-97

12. Microsoft SQL [Computer Software]. Version 18.12.1. Washington: Microsoft; 2022.

13. Rosenfield RL, Lipton RB, Drum ML. Thelarche, pubarche, and menarche attainment in children with normal and elevated body mass index [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2009 Apr;123(4):1255]. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):84-88.

14. Steensma TD, Kreukels BP, de Vries AL, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Gender identity development in adolescence. Horm Behav. 2013;64(2):288-297.

15. Heiden-Rootes KM, Salas J, Scherrer JF, Schneider FD, Smith CW. Comparison of Medical Diagnoses among Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex-Partnered Patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):688-693.

Tables

Table 1.

Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation of Patient Population.

|

|

N (%)

|

|

Sex

|

|

Female

|

3,095,729 (53.7%)

|

|

Male

|

2,658,409 (46.2%)

|

|

Unknown

|

2,084 (<1.0)

|

|

Other

|

6 (<1.0)

|

|

Data Unavailable

|

411 (<1.0)

|

|

Gender Identity

|

|

Female

|

259,980 (4.5%)

|

|

Male

|

160,437 (2.8%)

|

|

Transgender Female

|

903 (<1.0)

|

|

Transgender male

|

1,421 (<1.0)

|

|

Genderqueer

|

583 (<1.0)

|

|

Gender Nonconforming

|

1,660 (<1.0)

|

|

Choose Not to Disclose

|

1,160 (<1.0)

|

|

Other

|

418 (<1.0)

|

|

Data Unavailable

|

5,330,077 (92.5%)

|

|

Sexual Orientation

|

|

Straight

|

232,148 (4.0%)

|

|

Lesbian

|

2,916 (<1.0)

|

|

Gay

|

3,508 (<1.0)

|

|

Lesbian or Gay

|

33 (<1.0)

|

|

Bisexual

|

7,322 (<1.0)

|

|

Multiple Listed

|

898 (<1.0)

|

|

Something Else

|

1,633 (<1.0)

|

|

Don’t Know

|

2,244 (<1.0)

|

|

Choose Not to Disclose

|

9,656 (<1.0)

|

|

Data Unavailable

|

5,496,281 (95.4%)

|

Author Biographies

Whitney Linsenmeyer, PhD, RD, LD (she/her) is an assistant professor of nutrition at Saint Louis University and co-founder of the Transgender Health Collaborative at SLU. Her research centers on gender-affirming nutrition care for the transgender population.

Katie Heiden-Rootes, PhD, LMFT (she/her) is an assistant vice president in the division of diversity & innovative community engagement at Saint Louis University and an associate professor of medical family therapy. She co-founded the Transgender Health Collaborative at SLU and centers her scholarship on the mental health and well-being of queer youth and their families.

Michelle R. Dalton, PhD, LPC (they/them) is an assistant professor of medical family therapy at Saint Louis University and a member of the Transgender Health Collaborative at SLU. Their research areas focus on gender identity and racial minority stress and transgender health.

Timothy Chrusciel, MPH (he/him) is a biostatistician with Saint Louis University’s Advanced HEAlth Data (AHEAD) Research Institute. He has over 15 years of experience in a wide range of statistical methodologies.